Ostensibly about teaching, this #100DaysToFall series has been a delightful daily challenge to muse over what a teaching-obsessed college professor’s summer life looks like. For the most part, it looks nearly identical to the middle-of-the-semester life, save formal class meetings and the endless waves of guilt for not giving students feedback more quickly. I spend a lot of time thinking, reading, communicating with students, tweaking my pedagogy, talking with colleagues, brainstorming ideas to improve all of those things, and so forth.

But May — long my favorite month of the year — often brings unexpected insights, and I’m in the midst of harvesting those right now. Today’s post is all about what happens when a student-centered teacher takes a couple of days to check out of her daily routine and tries to reach someone who does not want to be reached. It could be a parable of community college teaching, and in some ways it is. But it’s also about living in this messy, complex, too-often disappointing world.

So here we go.

The backstory

Four years ago tomorrow, my parents and I bundled up in my mom’s minivan and made for Kansas City. It’s the adopted home city of my MUCH beloved (and endlessly frustrating) younger brother, whom I shall herein refer to as George (IYKYK, as the kids say). If you want to have your heart broken before you even get into the heart of this blog post, go read this one, written about the feelings that prompted that trip — but enter knowing that I can’t even get halfway through it without waterworks, so you were warned.

And if you want even more context and an after-action report, here’s what I wrote in late May 2017, after that trip.

But the long and short of it is this: My brother has been incommunicado for basically all of the last 5-6 years, give or take, and nobody knows why, and none of my family (to my knowledge) is in touch with him, and it is heartbreaking and maddening and incomprehensible and all of the feels (none especially positive or hopeful).

This perhaps hurts all the more because I adore this man so much. It’s not just that I love George because he’s my brother; he’s objectively a delightful human to know and love. He’s clever, loving, loyal, and quirky. He has one of the most expressive faces I’ve ever seen; a tiny facial change communicates volumes. I love him fiercely and fully, with everything I am.

Every four years?

So… yesterday, I loaded up my car in southern middle Tennessee and headed to Kansas City. I told very, very few people about this trip before leaving. Mostly, that’s because answering questions about George is emotionally exhausting. The world — including me — doesn’t deal well with uncertainty or inexplicable phenomena. We need a reason, and if we cannot find one, our human brains invent one (and then engages in an exhaustive background process of justifying why that explanation is obvious). When George comes up in conversation, or when someone is reminded of him, it’s always some version of: “Have you heard from your brother recently” and then devolves into, “What’s going on with him?”

My goodness, would I ever love to answer that question!!

But I cannot. I am not living inside his brain, and I don’t have access to it, so I can only speculate. And, for reasons I’ll explore momentarily, my speculation is perhaps slightly more informed than yours, but it’s also untrustworthy because I have an emotional stake in what theory we land upon.

Hence the furtive road trip. Doug, two friends, and my parents knew I was venturing to KC, but nobody else did. Frankly, I can’t trust the world with that knowledge, not at a time when my focus needed to be on ensuring I didn’t completely fall apart.

(Side note: I haven’t. Please don’t ask for updates; these convos are freaking hard.)

So I’m here. In Kansas City. (Currently working at a small table outside a Starbucks, because apparently the Starbucks corporation doesn’t trust CDC guidance and isn’t prepared to let the fully vaccinated work inside just yet, BOOO!)

I’ve been by his house (according to Kansas property records) twice, and I once found a car outside. At no time have I gotten an answer to door knocks, nor have I made visual contact with him. I’ll try again tonight (after work hours), but it seems quite likely that this will be another failure of a trip to try to see George. I’m not surprised — I came expecting that — but I am sad.

And, it seems, perhaps a trip every four years might be the right frequency. <shrug>

‘A culture of caring’

In the midst of all this driving around town (I planned my trip by scoping out used bookstores, the local IKEA, and other delightful points of interest) and not hanging out with George, I’ve been listening to some fascinating things. Earlier today, I listened to an American Association of Community Colleges podcast episode with Amarillo College’s president Russell Lowery-Hart. The discussion revolved around Amarillo’s “culture of caring,” which has become something of a movement among community colleges (including mine). A few things in that conversation really got me thinking about similarities in how I relate to George and my students.

For starters, any teacher worth her salt is motivated to connect with and have an impact on her students; similarly, any sister with a heart wants the same with her brother. In both cases, sometimes the object of our care starts to drift away, for whatever reason. Try as we might — and sometimes, we try really, Really, REALLY freaking hard — we cannot force those who are drifting to return. The adage you’ll hear teachers share with one another, when one of us is lamenting a student who feels lost to us: “You can’t reach someone who doesn’t want to be reached.”

And as utterly devastating it is, right now, for whatever reason, George doesn’t want to be reached.

As Dr. Lowery-Hart urges, we can and should love our students as they are; it does none of us any good to love the students we wish we had, or that we once had, or that we might someday in the future have. At this moment, our necessary role is to love whoever shows up, in whatever way they show up, and communicate through our actions and words that we believe in them.

Similarly, in this moment, I have to love George as he is, not as he once was or as I hope, one day, he will be. Right now, he is not an active part of my life. He’s making choices I don’t understand, and I don’t have any effective means of impacting his life. To reconcile myself to this reality hurts; I know I could love him more, if I had access to him, and I know it would make me happier if I were allowed to. But I’m not. Critically, i’s not within my power to change this.

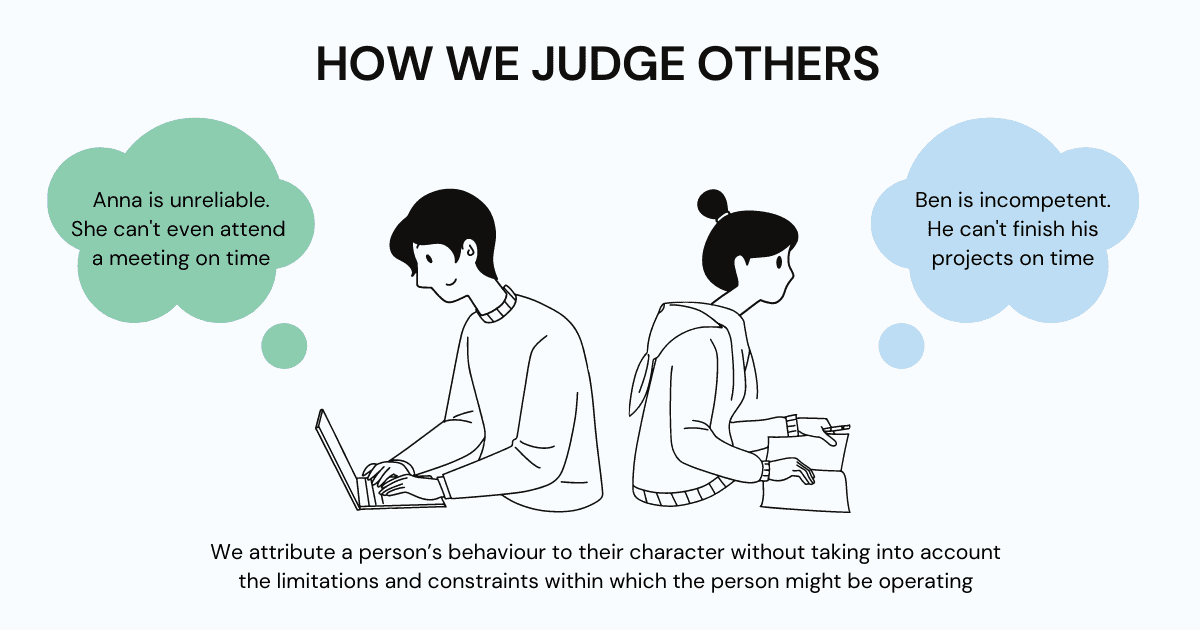

In such situations, we so often try to negotiate our way out of this powerlessness by imputing motives upon others, such as on our MIA students. We say things like, “They just don’t want it enough” or “their priorities are off” or “they aren’t ready for college.” It’s a way of coddling ourselves, of making ourselves feel better, of reasserting some order and clarity around things hidden from our view.

It’s what psychologists call the fundamental attribution error:

Because we cannot see the full range of thoughts and circumstances in others, we make assumptions about their behavior that are often wildly inaccurate.

I mention this because it’s something we need to keep in mind in every relationship. As Glennon Doyle says in her book Untamed, nobody else can tell someone how they should live their lives, because — and this is really key — nobody has ever lived another person’s life. We have no authority to tell our students what they should do, just as I have no authority to tell my brother what kind of relationship he should have with me, because I have literally no idea — especially after all these estranged years — what the unique combination of experiences, thoughts, and feelings he’s experiencing are like. Glennon writes:

Every life is an unprecedented experiment. This life is mine alone. So I have stopped asking people for directions to places they’ve never been.

If my life is mine alone, then George’s life is his alone. It impacts me, yes, but he is not responsible for my emotions, just as I am not responsible for his. (See Eleanor Roosevelt, “No one can make you feel inferior without your consent.”)

Our students’ lives are theirs alone, too. We want to be a force for inspiration, for positive change, for hope, for encouragement, for love … but ultimately, it falls on the student to accept or reject our presence in their lives.

Glennon urges us to feel our feelings, saying that suffering comes when we try to avoid them. So here I am, in Kansas City for another night, feeling my feelings — A-L-L of them: the sadness, yes, but also the joy of IKEA, the irritation at my wet shoes after the rain began, and the excitement to see my fully-vaccinated parents after COVID kept us apart for 18 months.

Thanks for reading my #100DaysToFall post. Check out more by wandering over to the page that collects my teaching blog posts. And come back soon — maybe tomorrow (?) — to journey to the fall 2021 semester with me.